The Devonian period, which was 419 million to 359 million years ago, is best known for Tiktaalik, the lobe-finned fish that is often portrayed pulling itself onto land. However, the “age of the fishes,” as the period is called, also saw evolutionary progress in plants. Researchers reporting August 8 in the journal Current Biology describe the largest example of a Devonian forest, made up of 250,000 square meters of fossilized lycopsid trees, which was recently discovered near Xinhang in China’s Anhui province. The fossil forest, which is larger than Grand Central Station, is the earliest example of a forest in Asia.

[ad_336]

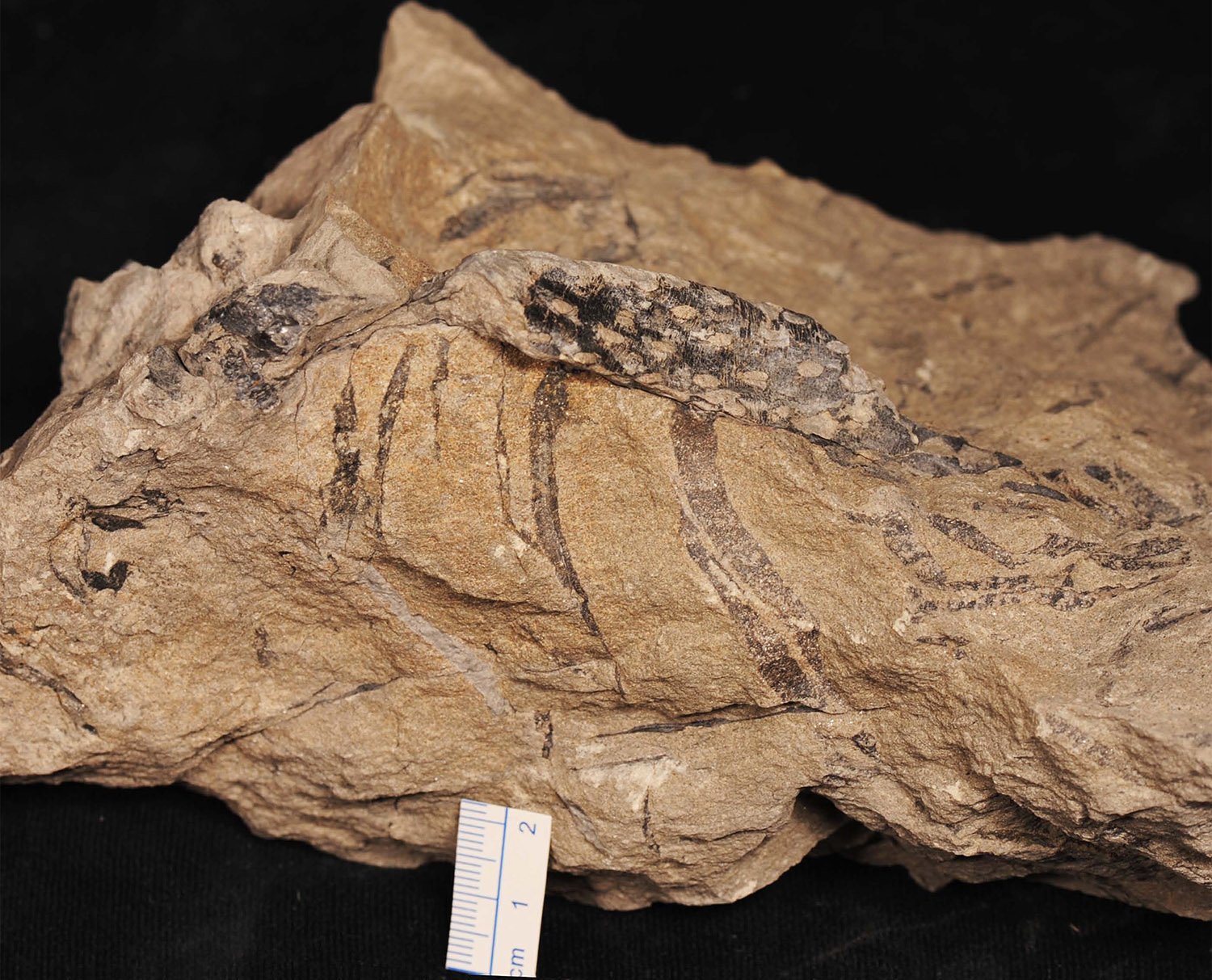

Lycopsids found in the Xinhang forest resembled palm trees, with branchless trunks and leafy crowns, and grew in a coastal environment prone to flooding. These lycopsid trees were normally less than 3.2 meters tall, but the tallest was estimated at 7.7 meters, taller than the average giraffe. Giant lycopsids would later define the Carboniferous period, which followed the Devonian, and become much of the coal that is mined today. The Xinhang forest depicts the early root systems that made their height possible. Two other Devonian fossil forests have been found: one in the United States, and one in Norway.

“The large density as well as the small size of the trees could make Xinhang forest very similar to a sugarcane field, although the plants in Xinhang forest are distributed in patches,” says Deming Wang, a professor in the School of Earth and Space Sciences at Peking University, co-first author on the paper along with Min Qin of Linyi University. “It might also be that the Xinhang lycopsid forest was much like the mangroves along the coast, since they occur in a similar environment and play comparable ecologic roles.”

[rand_post]

The fossilized trees are visible in the walls of the Jianchuan and Yongchuan clay quarries, below and above a four-meter thick sandstone bed. Some fossils included pinecone-like structures with megaspores, and the diameters of fossilized trunks were used to estimate the trees’ heights. The authors remarked that it was difficult to mark and count all the trees without missing anything.

“Jianchuan quarry has been mined for several years and there were always some excavators working at the section. The excavations in quarries benefit our finding and research. When the excavators stop or left, we come close to the highwalls and look for exposed erect lycopsid trunks,” says Wang, who, with Qin, found the first collection of fossil trunks in the mine in 2016. “The continuous finding of new in-situ tree fossils is fantastic. As an old saying goes: the best one is always the next one.”