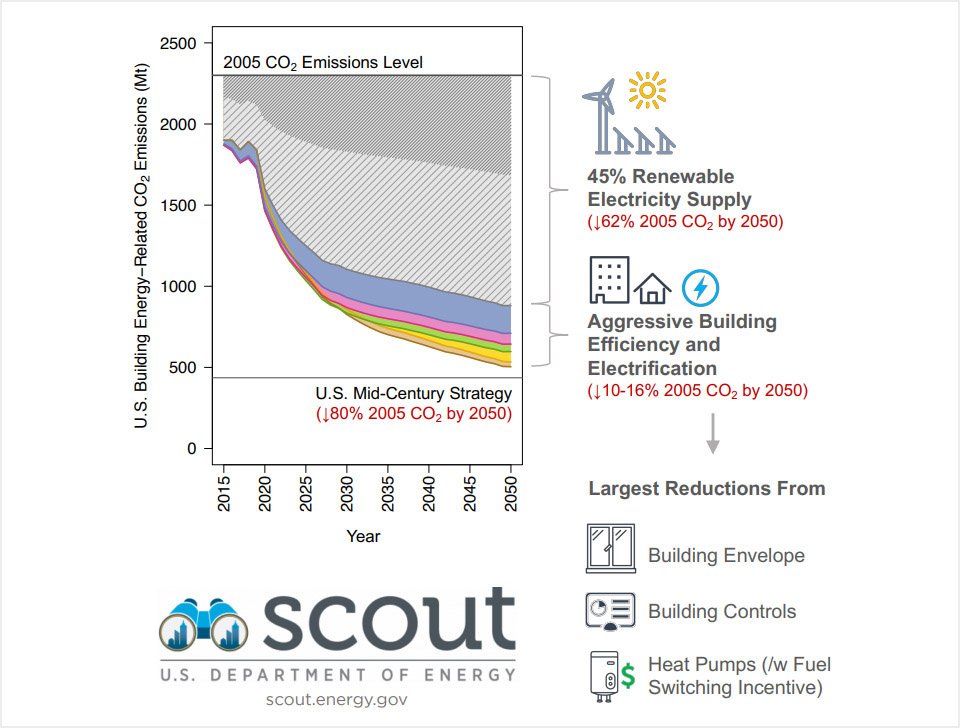

Energy use in buildings – from heating and cooling your home to keeping the lights on in the office – is responsible for over one-third of all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the United States. Slashing building CO2 emissions 80% by 2050 would therefore contribute significantly to combatting climate change. A new model developed by researchers at two U.S. national laboratories suggests that reaching this target will require the installation of highly energy-efficient building technologies, new operational approaches, and electrification of building systems that consume fossil fuels directly, alongside increases in the share of electricity generated from renewable energy sources. Their work appears August 15 in the journal Joule.

“Buildings are a substantial lever to pull in trying to reduce total national CO2 emissions since they are responsible for 36% of all energy-related emissions in the U.S.,” says Jared Langevin, a research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and lead author of the study. “Because the buildings sector uses energy in a multitude of ways and is responsible for such a large share of electricity demand, buildings can help accelerate the cost-effective integration of clean electricity sources on top of contributing direct emissions reductions through reduced energy use.”

To estimate the magnitude of possible CO2 emissions reductions from the U.S. buildings sector over several decades, the researchers considered three types of efficiency measures – technologies with higher energy performance than typical alternatives, such as dynamic windows and air sealing of walls, sensing and control strategies that improve the efficiency of building operations, and conversion of fuel-fired heating and water heating equipment to comparable systems that can run on electricity. They also considered how parallel incorporation of renewable energy sources into the electric grid would shift emissions reduction estimates from each building efficiency measure and the buildings sector as a whole.

[ad_336]

“While building CO2 emissions are quite sensitive to the greenhouse gas intensity of the electricity supply, measures that improve the efficiency of energy demand from buildings need to be part of the solution,” Langevin says.

“Getting close to the 80% emissions reduction target requires concurrent reductions in building energy demand, electrification of this demand, and substantial penetration of renewable sources of electricity – nearly half of annual electricity generation by 2050. Moreover, buildings can support the cost-effective integration of variable renewable sources by offering flexibility in their operational patterns in response to electric grid needs.”

Examining results for specific efficiency measures, the researchers identified two particularly promising avenues for reducing emissions. The first involves energy-saving retrofits and upgrades to walls, windows, roofs, and insulation – the so-called building “envelope” – approaches that can also boost living and working comfort for building occupants. The second focuses on smart software that is capable of optimizing when, where, and to what degree energy-intensive building heating, cooling, lighting, and ventilation services should be provided.

[rand_post]

The researchers stress that bringing these strategies and emissions benefits to fruition is contingent upon complementary action by policymakers, manufacturers and vendors, building service professionals, and consumers. “Regulations and incentives that support the sale of more efficient, less carbon-intensive technology options, early-stage research and development that drives breakthroughs in technology performance, aggressive marketing of those technologies once developed, training for local contractors charged with technology installation, and consumer willingness to consider purchasing newer options on the market are all needed to achieve the 80% emissions reduction goal by 2050,” says Langevin.

To promote the transparency and repeatability of their analysis, the researchers have published their efficiency measures and results data, all generated using Scout, a model that is annually updated to reflect key changes in the building energy use and electricity supply landscapes. “We look forward to periodically revisiting this analysis to reassess where emissions from the buildings sector stand relative to the 2050 target, under both business-as-usual and more optimistic scenarios of efficient technology adoption and renewable electricity supply,” Langevin says.