For polar bears, the insulation provided by their fat, skin, and fur is a matter of survival in the frigid Arctic. For engineers, polar bear hair is a dream template for synthetic materials that might lock in heat just as well as the natural version. Now, materials scientists in China have developed such an insulator, reproducing the structure of individual polar bear hairs while scaling toward a material composed of many hairs for real-world applications in the architecture and aerospace sectors. Their work appears June 6 in the journal Chem.

“Polar bear hair has been evolutionarily optimized to help prevent heat loss in cold and humid conditions, which makes it an excellent model for a synthetic heat insulator,” says co-senior author Shu-Hong Yu, a professor of chemistry at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC).

“By making tube aerogel out of carbon tubes, we can design an analogous elastic and lightweight material that traps heat without degrading noticeably over its lifetime.”

Unlike the hairs of humans or other mammals, polar bear hairs are hollow. Zoomed in under a microscope, each one has a long, cylindrical core punched straight through its center. The shapes and spacing of these cavities have long been known to be responsible for their distinctive white coats. But they also are the source of remarkable heat-holding capacity, water resistance, and stretchiness, all desirable properties to imitate in a thermal insulator.

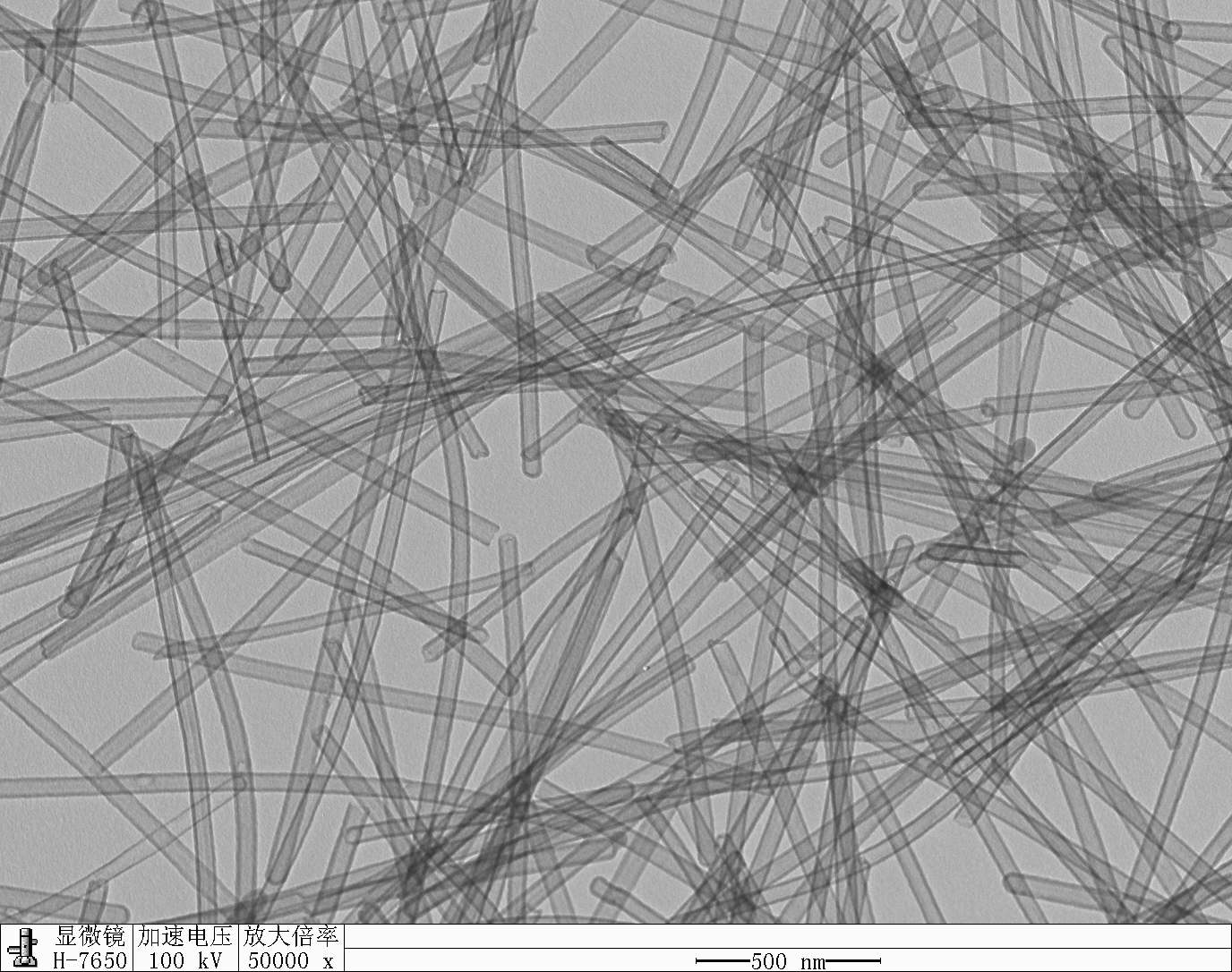

“The hollow centers limit the movement of heat and also make the individual hairs lightweight, which is one of the most outstanding advantages in materials science,” says Jian-Wei Liu, an associate professor at USTC. To emulate this structure and scale it to a practical size, the research team–additionally co-led by Yong Ni, a mechanical engineering professor at USTC–manufactured millions of hollowed-out carbon tubes, each equivalent to a single strand of hair, and wound them into a spaghetti-like aerogel block.

[rand_post]

Compared to other aerogels and insulation components, they found that the polar-bear-inspired hollow-tube design was lighter in weight and more resistant to heat flow. It was also hardly affected by water–a handy feature both for keeping polar bears warm while swimming and for maintaining insulation performance in humid conditions. As a bonus, the new material was extraordinarily stretchy, even more so than the hairs themselves, further boosting its engineering applicability.

Scaling up the manufacturing process to build insulators on the meter scale rather than the centimeter one will be the next challenge for the researchers as they aim for relevant industrial uses. “While our carbon-tube material cannot easily be mass produced at the moment, we expect to overcome these size limitations as we work toward extreme aerospace applications,” says Yu.