The question whether light consists of particles or instead propagates as a wave through a medium has been the subject of scientific debate throughout most of the history of science. In the 20th century it finally has been established that light can be indeed both, particle and wave, but not at the same time. Still, the nature of light keeps challenging both our understanding and intuition. A case in point are results that researchers from the National Laboratory of Solid-State Microstructures, the School of Physics and the Collaborative Innovation Center of Advanced Microstructures of Nanjing University (China) report today online in the journal Nature Photonics.

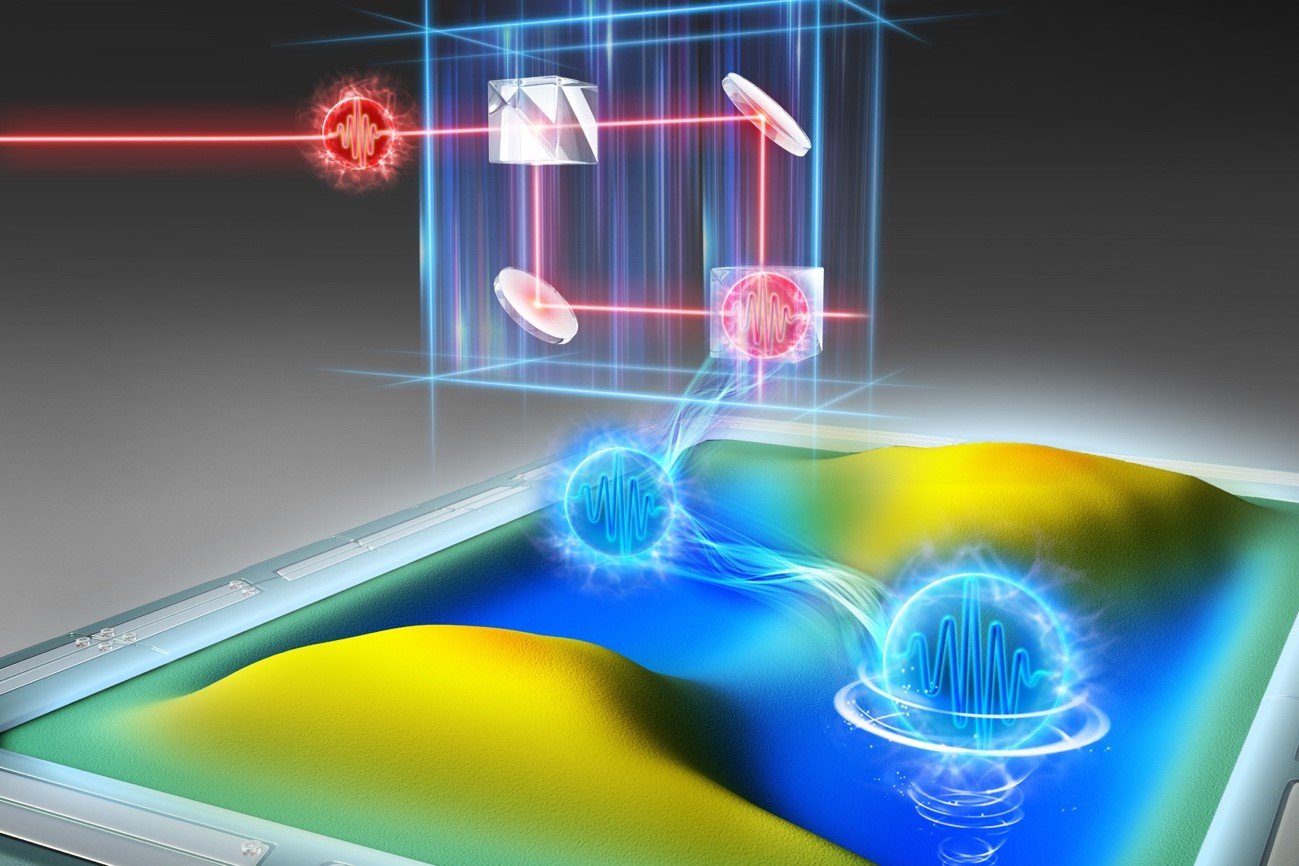

In an experiment that involved optical equipment in two laboratories that are 141 metres apart from each other, the team led by Dr. Xiao-Song Ma demonstrated conclusively that light can not only be in wave or particle states, but also in a quantum superposition of the two. Moreover, they showed that the properties of this quantum wave–particle superposition can be tuned, opening up the prospect of ultimately exploiting the new experimental capability in quantum technologies.

Light surprises

The debate on the nature of light has kept many great scientists busy over the centuries. Euclid and Ptolemy have made contributions, as did Descartes, Newton, and many other protagonists of the history of science. To explain how shadows form, for instance, light is best considered to consist of particles. By contrast, interference effects—most notably in the double-slit experiments of Thomas Young at the beginning of the 19th century—bring the wave nature of light to full display. The advent of quantum physics in the 20th century finally provided a framework to understand particles and waves as dual states of light.

[ad_336]

But even a century on, surprising phenomena emerge from the wave–particle duality. A famed example is the delayed-choice thought experiment, originally proposed by John Archibald Wheeler and further developed by other physicists. In that thought experiment, an external observer can choose (by changing one component of the experiment) whether single quanta of light, so-called photons, behave as particles or as waves. Intriguingly, the choice between particle and wave states can be delayed to until after the photon enters the experimental setup.

“The experiment dramatically underscores the different conceptions of space and time in classical and quantum physics, which is one of the most intriguing effects in quantum mechanics”, says Ma.

Thought-provoking experiments

In recent years, Wheeler’s thought experiment and variants of it have been implemented in practice. And there is more to come. Ma: “Thanks to the rapid development of optical technology, it has not only become possible to realize such thought experiments, but also to design new ones.” And designing a new experiment is what Ma and his team did. Building on earlier work, they developed a quantum version of the delayed-choice experiment, where wave and particle states of single photons are placed in coherent superposition.

The key to achieve such a mixture of particle and wave states is to use quantum states of additional photons to control the component that allows switching between wave and particle. But that ‘quantum-controlled choice’ can only be considered truly independent if the control unit is placed so far away from the main experiment that it could not possibly interfere with the rest of the experiment. Physicists speak of ‘Einstein locality conditions’ being ensured.

[rand_post]

Particle–wave duality on the next level

The experiment of the Nanjing group is the first quantum delayed-choice experiment under strict Einstein locality conditions. Achieving that required connecting equipment located in two separate labs, 141 metres away from one another.

“By carefully arranging the location and timing of the experimental setup, we achieved the required relativistic separations between relevant events,” says Kai Wang, a PhD student in Ma’s group and first author of the Nature Photonics paper.

With this experiment the team directly and unambiguously established the quantum nature of superpositions between wave and particle states of light, and also showed how key properties of that superposition can be tuned. Their demonstration therefore is of fundamental importance to quantum optics and at the same time paves the way for realizing non-local control of quantum systems in the context of future quantum technologies.