A historic 120-year-old data set is allowing researchers to confirm what data modeling systems have been predicting about climate change: Climate change is increasing precipitation events like hurricanes, tropical storms and floods.

Researchers analyzed a continuous record kept since 1898 of tropical cyclone landfalls and rainfall associated with Coastal North Carolina storms. They found that six of the seven highest precipitation events in that record have occurred within the last 20 years, according to the study.

“North Carolina has one of the highest impact zones of tropical cyclones in the world, and we have these carefully kept records that shows us that the last 20 years of precipitation events have been off the charts,” said Hans Paerl, Kenan Professor of Marine and Environmental Sciences at the UNC-Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences.

Paerl is lead author on the paper, “Recent increase in catastrophic tropical cyclone flooding in coastal North Carolina, USA: Long-term observations suggest a regime shift,” published July 23 in Nature Research’s Scientific Reports.

Three storms in the past 20 years – hurricanes Floyd, Matthew and Florence – resulted in abnormally large floods. The probability of these three flooding events occurring in such a short time period is 2%, according to the study.

This frequency suggests that “three extreme floods resulting from high rainfall tropical cyclone events in the past 20 years is a consequence of the increased moisture carrying capacity of tropical cyclones due to the warming climate,” the study said.

In addition to the growing number of storms and floods, an increasing global population is compounding the problem by driving up emissions of greenhouse gases, leading to increases in ocean temperature, evaporation and subsequent increases in precipitation associated with tropical cyclones.

Increasing rainfall

North Carolina has seen an increase in unprecedentedly high rainfall since the late 1990s. The state also has seen an increase in higher rainfall from tropical cyclones over the past 120 years, according to the study.

[ad_336]

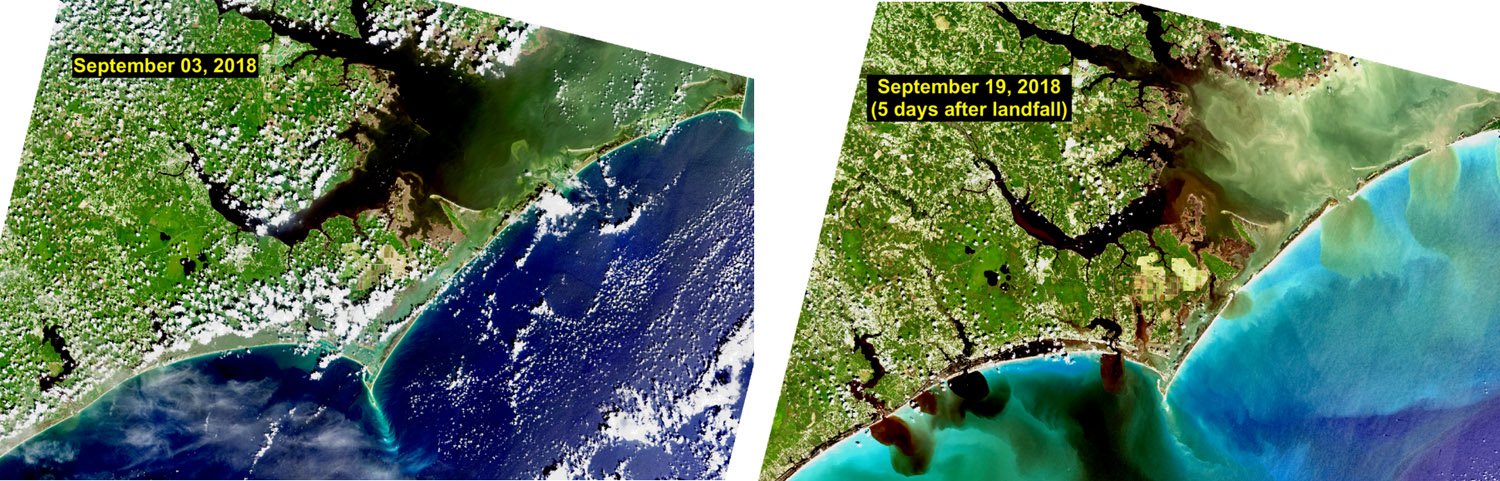

“The price we’re paying is that we’re having to cope with increasing levels of catastrophic flooding,” Paerl said. “Coastal watersheds are having to absorb more rain. Let’s go back to Hurricane Floyd in 1999, which flooded half of the coastal plain of North Carolina. Then, we had Hurricane Matthew in 2016. Just recently we had Hurricane Florence in 2018. These events are causing a huge amount of human suffering, economic and ecological damage.”

Part of that damage comes from how frequently storms hit the coast, Paerl said. This frequency means communities and ecosystems are challenged with rebuilding and rebounding before the next storm hits. The storms themselves don’t have to be intense, massive hurricanes, Paerl said. A Category 1 storm with intensive rainfall can cause huge amounts of damage.

The increasing rainfall means more runoff going into estuarine and coastal waters, like the Neuse River Estuary, and downstream Pamlico Sound, the USA’s second largest estuarine complex and a key Southeast fisheries nursery. More runoff means more organic matter and nutrient losses from soil erosion, farmland and animal operations, urban centers and flushing of swamps and wetlands. This scenario increases the overloading of organic matter and nutrients that ecosystems can’t process quickly enough to avoid harmful algal blooms, hypoxia, fish and shellfish kills.

Increasing population

Additionally, North Carolina’s population is growing. The state has more than 10.3 million residents, according to 2018 U.S. Census data. In 1990, North Carolina had 6.6 million residents.

“We are in part responsible for what’s going on in the context of fossil fuel combustion emissions that are leading to global warming,” Paerl said. “The ocean is a huge reservoir that is absorbing heat and seeing more evaporation. With more evaporation comes more rainfall.”

[rand_post]

Previous research from Paerl’s team has shown that heavy rainfall events and tropical storms lead to more organic materials being transferred from land to ocean. As those materials are processed and decomposed by estuarine and coastal waters, more carbon dioxide is generated and vented back up into the atmosphere, where it can add to already rising carbon dioxide levels. These effects can last for weeks to months after a storm’s passage.

“We can help minimize the harmful effects of a ‘new normal’ of wetter storm events,” Paerl said. “Curbing losses of organic matter and nutrients by vegetative buffers around farmlands and developed areas prone to storm water runoff, minimizing development in floodplains and avoiding fertilizer applications during hurricane season, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions are positive steps which we can all contribute to.”