It was the most serious release of radioactive material since Fukushima 2011, but the public took little notice of it: In September 2017, a slightly radioactive cloud moved across Europe. Now, a study has been published, analyzing more than 1300 measurements from all over Europe and other regions of the world to find out the cause of this incident. The result: it was not a reactor accident, but an accident in a nuclear reprocessing plant. The exact origin of the radioactivity is difficult to determine, but the data suggests a release site in the southern Urals. This is where the Russian nuclear facility Majak is located. The incident never caused any kind of health risks for the European population.

Among the 70 experts from all over Europe who contributed data and expertise to the current study are Dieter Hainz and Dr. Paul Saey from the Institute of Atomic and Subatomic Physics at TU Wien (Vienna). The data was evaluated by Prof. Georg Steinhauser from the University of Hanover (who is closely associated with the Atomic Institute) together with Dr. Olivier Masson from the Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire (IRSN) in France. The team has now published the results of the study in the renowned journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (PNAS).

Unusual ruthenium release

“We measured radioactive ruthenium-106,” says Georg Steinhauser. “The measurements indicate the largest singular release of radioactivity from a civilian reprocessing plant.”

In autumn of 2017, a cloud of ruthenium-106 was measured in many European countries, with maximum values of 176 millibecquerels per cubic meter of air. The values were up to 100 times higher than the total concentrations measured in Europe after the Fukushima incident. The half-life of the radioactive isotope is 374 days.

[rand_post]

This type of release is very unusual. The fact that no radioactive substances other than ruthenium were measured is a clear indication that the source must have been a nuclear reprocessing plant.

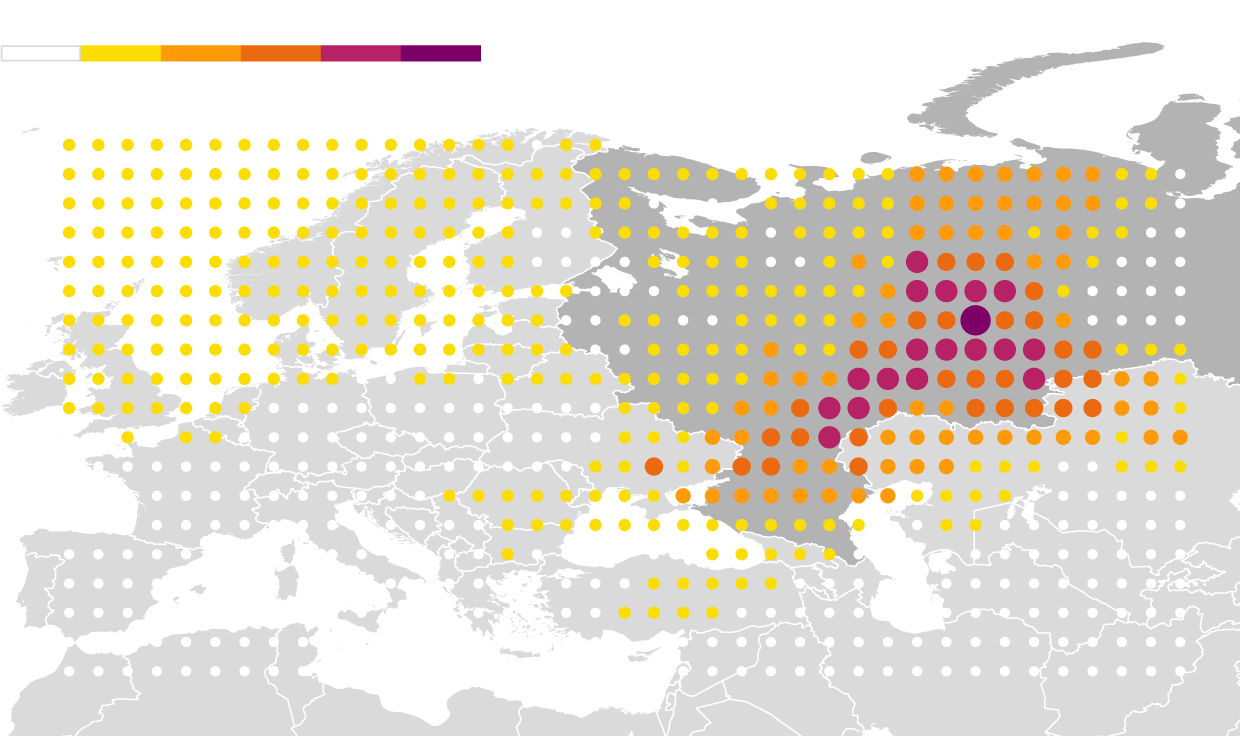

The geographic extent of the ruthenium-106 cloud was also remarkable – it was measured in large parts of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia and the Arabian Peninsula. Ruthenium-106 was even found in the Caribbean. The data was compiled by an informal, international network of almost all European measuring stations. In total, 176 measuring stations from 29 countries were involved. In Austria, in addition to TU Wien, the AGES (Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety) also operates such stations, including the alpine observatory at Sonnblick at 3106m above sea level.

No health hazard

As unusual as the release may have been, the concentration of radioactive material has not reached levels that are harmful to human health anywhere in Europe. From the analysis of the data, a total release of about 250 to 400 terabecquerel of ruthenium-106 can be derived. To date, no state has assumed responsibility for this considerable release in the fall of 2017.

[ad_336]

The evaluation of the concentration distribution pattern and atmospheric modelling suggests a release site in the southern Urals. This is where the Russian nuclear facility Majak is located. The Russian reprocessing plant had already been the scene of the second-largest nuclear release in history in September 1957 – after Chernobyl and even larger than Fukushima. At that time, a tank containing liquid waste from plutonium production had exploded, causing massive contamination of the area.

Olivier Masson and Georg Steinhauser can date the current release to the time between 25 September 2017, 6 p.m., and 26 September 2017 at noon – almost exactly 60 years after the 1957 accident.

“This time, however, it was a pulsed release that was over very quickly,” says Professor Steinhauser.

In contrast, the releases from Chernobyl or Fukushima lasted for days. “We were able to show that the accident occurred in the reprocessing of spent fuel elements, at a very advanced stage, shortly before the end of the process chain,” says Georg Steinhauser. “Even though there is currently no official statement, we have a very good idea of what might have happened.”