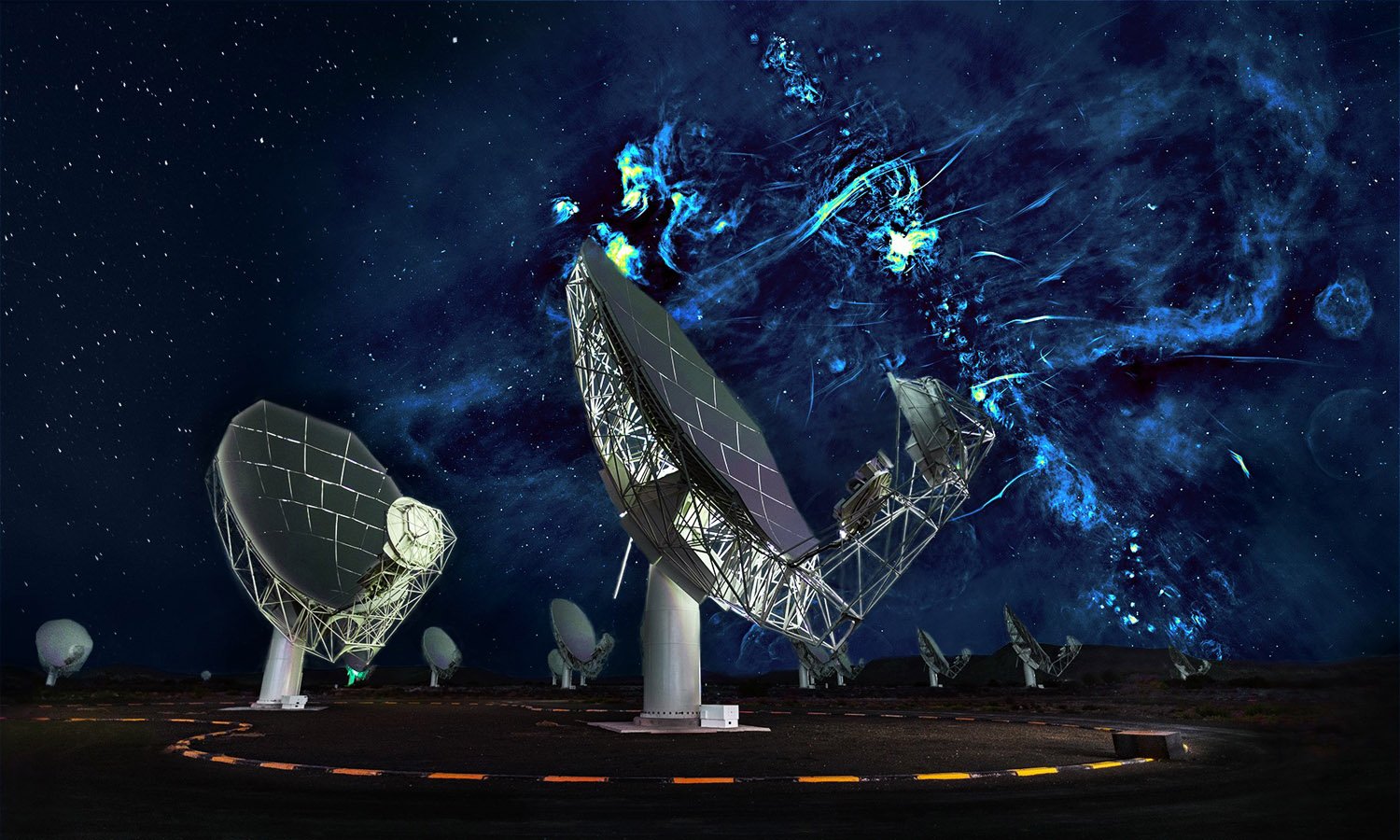

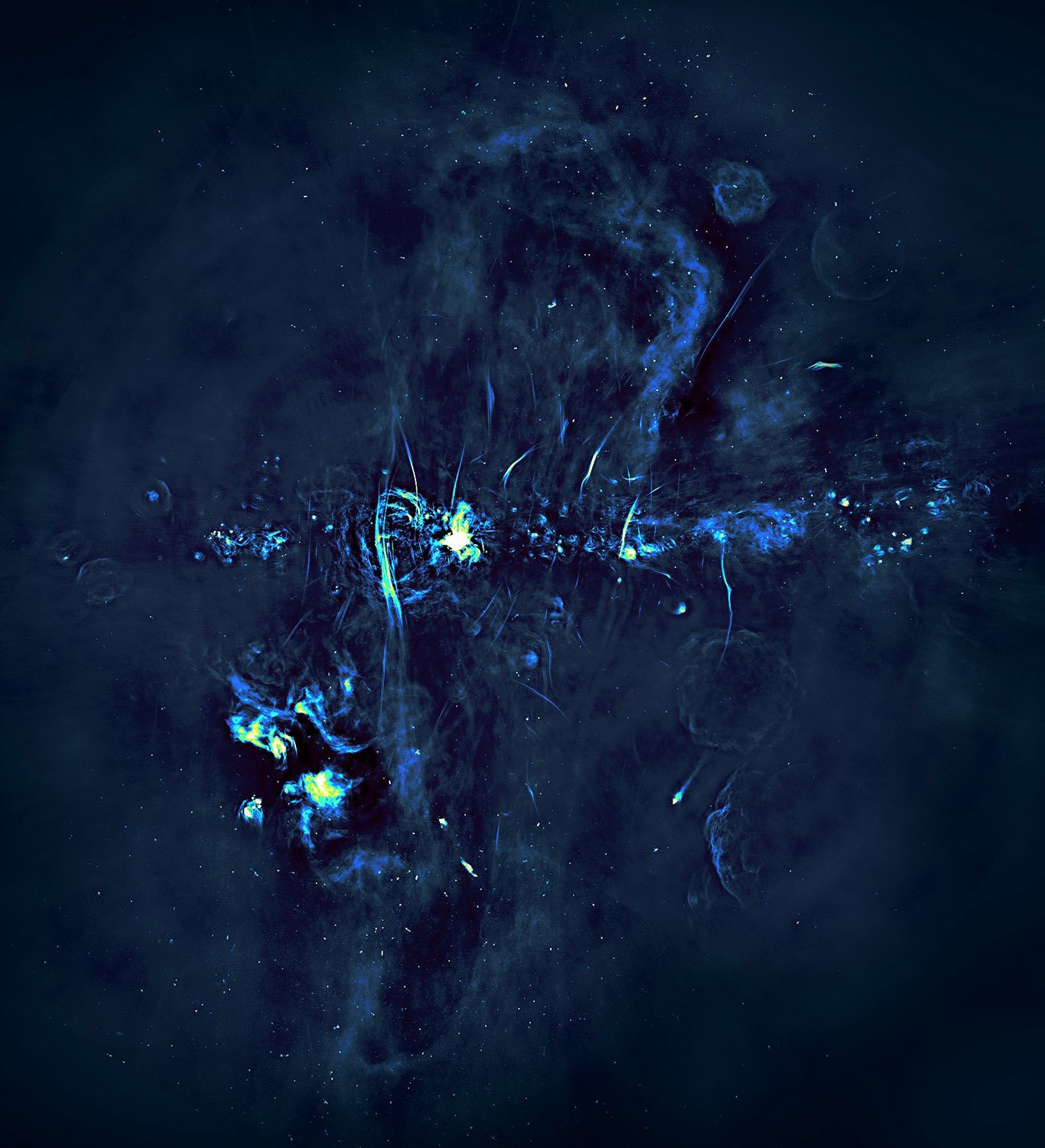

An international team of astronomers using the MeerKAT telescope has discovered enormous balloon-like structures that tower hundreds of light-years above and below the centre of our galaxy. Caused by a phenomenally energetic burst that erupted near the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole a few million years ago, the MeerKAT radio bubbles are shedding light on long-standing galactic mysteries.

“The centre of our galaxy is calm when compared to other galaxies with very active central black holes,” said Ian Heywood of the University of Oxford and lead author of an article appearing in the journal Nature today. “Even so, the Milky Way’s central black hole can – from time to time – become uncharacteristically active, flaring up as it periodically devours massive clumps of dust and gas. It’s possible that one such feeding frenzy triggered powerful outbursts that inflated this previously unseen feature.”

[ad_336]

Using the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO) MeerKAT telescope, Heywood and his colleagues mapped out broad regions in the centre of the galaxy, conducting observations at wavelengths near 23 centimeters. Radio emission of this kind is generated in a process known as synchrotron radiation, in which electrons moving at close to the speed of light interact with powerful magnetic fields. This produces a characteristic radio signal that can be used to trace energetic regions in space. The radio light seen by MeerKAT easily penetrates the dense clouds of dust that block visible light from the centre of the galaxy.

By examining the nearly identical extent and morphology of the twin bubbles, the researchers think they have found convincing evidence that these features were formed from a violent eruption that over a short period of time punched through the interstellar medium in opposite directions.

“The shape and symmetry of what we have observed strongly suggest that a staggeringly powerful event happened a few million years ago very near our galaxy’s central black hole,” said William Cotton, an astronomer with the US National Radio Astronomy Observatory and a co-author on the paper. “This eruption was possibly triggered by vast amounts of interstellar gas falling in on the black hole, or a massive burst of star formation which sent shockwaves careening through the galactic centre. In effect, this inflated bubbles in the hot, ionised gas near the galactic centre, energising it and generating radio waves that we eventually detect here on Earth.”

The environment surrounding the central black hole is vastly different than elsewhere in the Milky Way, and is a region of many mysteries. Among those are very long (tens of light-years) and narrow radio filaments found nowhere else, the origin of which has remained an unsolved puzzle since their discovery 35 years ago.

“The radio bubbles discovered by MeerKAT now shed light on the origin of the filaments,” said Farhad Yusef-Zadeh at Northwestern University in the USA, and a co-author of the paper. “Almost all of the more than 100 filaments are confined by the radio bubbles.”

[rand_post]

The authors suggest that the close association of the filaments with the bubbles implies that the energetic event that created the radio bubbles is also responsible for accelerating the electrons required to produce the radio emission from the magnetised filaments.

“These enormous bubbles have until now been hidden by the glare of extremely bright radio emission from the centre of the galaxy,” said Fernando Camilo of SARAO in Cape Town, and a co-author on the paper. “Teasing out the bubbles from the background noise was a technical tour de force, only made possible by MeerKAT’s unique characteristics and ideal location,” according to Camilo. “With this discovery, we’re witnessing in the Milky Way a novel manifestation of galaxy-scale outflows of matter and energy, ultimately governed by the central black hole.”

The discovery of the MeerKAT bubbles relatively nearby in the centre of our home galaxy brings astronomers one step closer to understanding spectacular activities that occur in more distant cousins of the Milky Way throughout the universe.

“It’s extremely gratifying that the first paper based on the full MeerKAT array is being published in the world’s leading science journal,” said Rob Adam, SARAO Managing Director. “Cutting-edge research instruments expand our views in unexpected ways, as this exciting discovery shows.”

“MeerKAT’s quality,” added Adam, “is a testament to the dedicated effort over 15 years by hundreds of people from South African research organisations, industry, universities, and government.”