The teeth of mammals experience constant wear. However, the details of these wear processes are largely unknown. Researchers at the University of Zurich have now demonstrated that the various areas of herbivores’ teeth differ in how susceptible they are to dental wear, detailing an exact chronology.

“In our clinic, we regularly treat guinea pigs and rabbits with dental problems. We’re therefore especially interested in finding out how exactly the changes to their teeth happen,” says Jean-Michel Hatt, professor at the Clinic for Zoo Animals, Exotic Pets and Wildlife at the University of Zurich.

The teeth of mammals are exposed to constant wear, but the exact details of this process have long been a mystery. Enamel is actually harder than the parts in the food that erode the teeth. In mammals, the relevant parts are mostly phytoliths, or “plant stones” – microscopic structures made of silica and often found in grass.

“There’s no consensus among dental researchers as to how phytoliths can actually erode tooth enamel,” says Jean-Michel Hatt.

Hard and softer dental tissue

The surfaces of teeth in herbivores are not only made of enamel. In between the enamel ridges, there is the dentin tissue, which is softer. As a result of these varying degrees of hardness, the chewing surface in the teeth of horses, cattle or guinea pigs develops a surface akin to a grater – with hard ridges protruding from softer tissue.

“There’s very little research into how this softer dentin tissue reacts to abrasive food,” says Hatt.

Most dental researchers are interested in the tooth enamel.

Guinea pigs and bamboo

[rand_post]

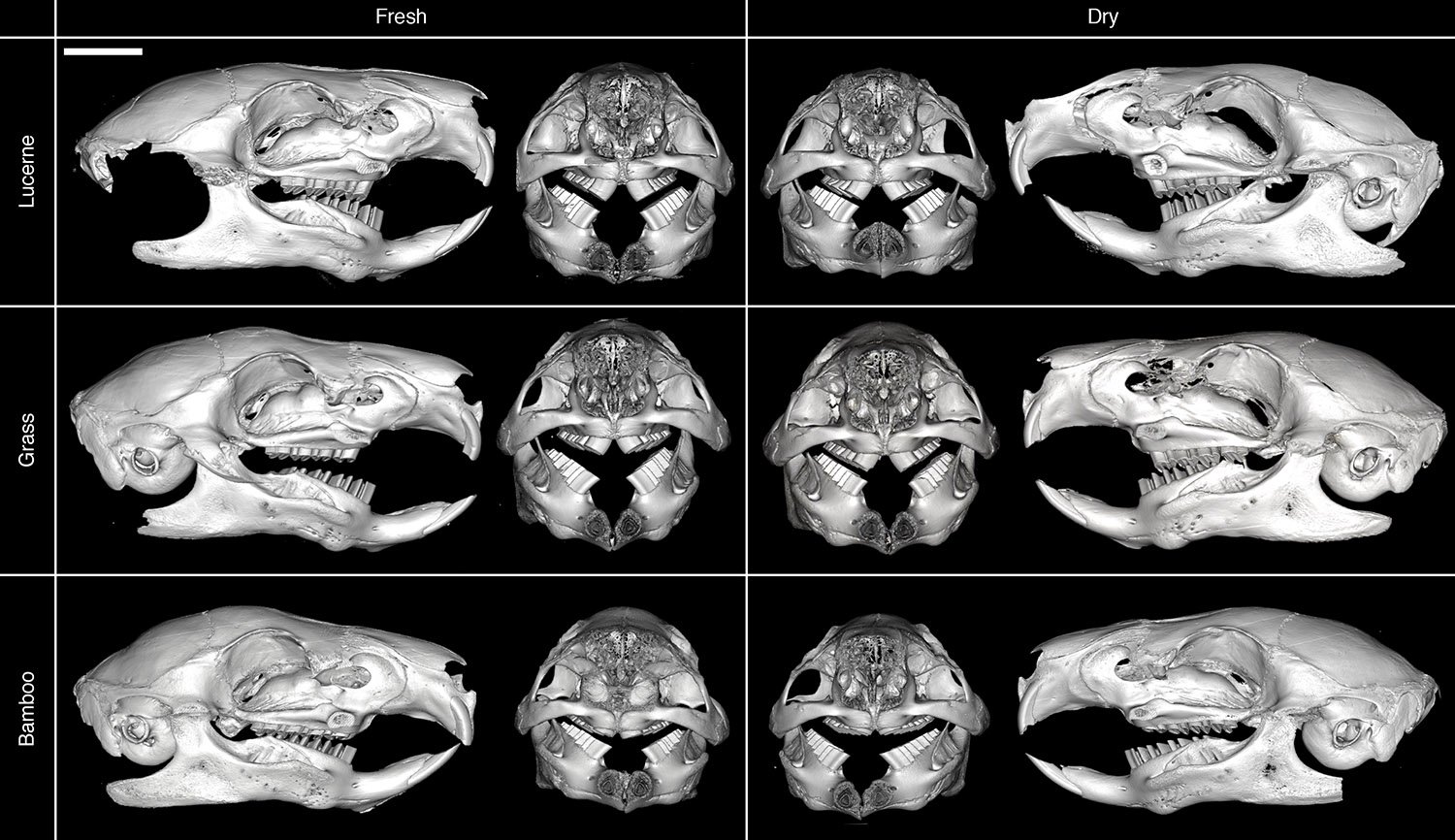

Working together with researchers from the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Jean-Michel Hatt and his team carried out a feeding experiment with guinea pigs. They fed the animals three different diets during three weeks, namely fresh lucerne – which, like clover, contains no phytoliths – normal grass and bamboo leaves. Bamboo in particular has a high silica content. To observe the effects, the researchers used micro-computed tomography, a particularly precise 3D imaging technique that uses X-rays to see inside an object.

The findings gained in this way impressed even the researchers.

“Even without knowing which animal I was surveying on screen, I was able to tell which diet it had been fed,” says Louise Martin, doctoral candidate at the Clinic for Zoo Animals, Exotic Pets and Wildlife. “The animals that had been given bamboo had significantly shorter teeth.”

[ad_336]

This was the case despite the fact that guinea pigs have continually growing molars. Taking a closer look, Martin found the decisive detail: The shorter teeth featured dentin surfaces that were disproportionately eroded.

“The phytoliths attack the dentin, and once the enamel ridges are very exposed, they’re no longer as stable and experience more wear.”

This is an effect that can likely only be observed well in systems with fast-growing teeth – in rodents, for example – and with extraordinarily abrasive types of food, such as bamboo.

“Most people don’t feed their herbivores bamboo,” says Hatt, “and our findings show that they’re right not to.” But what about animals such as panda bears, whose diet consists exclusively of bamboo? “Panda bears are actually carnivores and as such don’t have the ridged teeth typical of herbivores,” explains Jean-Michel Hatt. “Their teeth are fully covered by enamel.”