They are reminiscent of the “tractor beam” in Star Trek: special light beams can be used to manipulate molecules or small biological particles. Even viruses or cells can be captured or moved. However, these optical tweezers only work with objects in empty space or in transparent liquids. Any disturbing environment would deflect the light waves and destroy the effect. This is a problem, in particular with biological samples because they are usually embedded in a very complex environment.

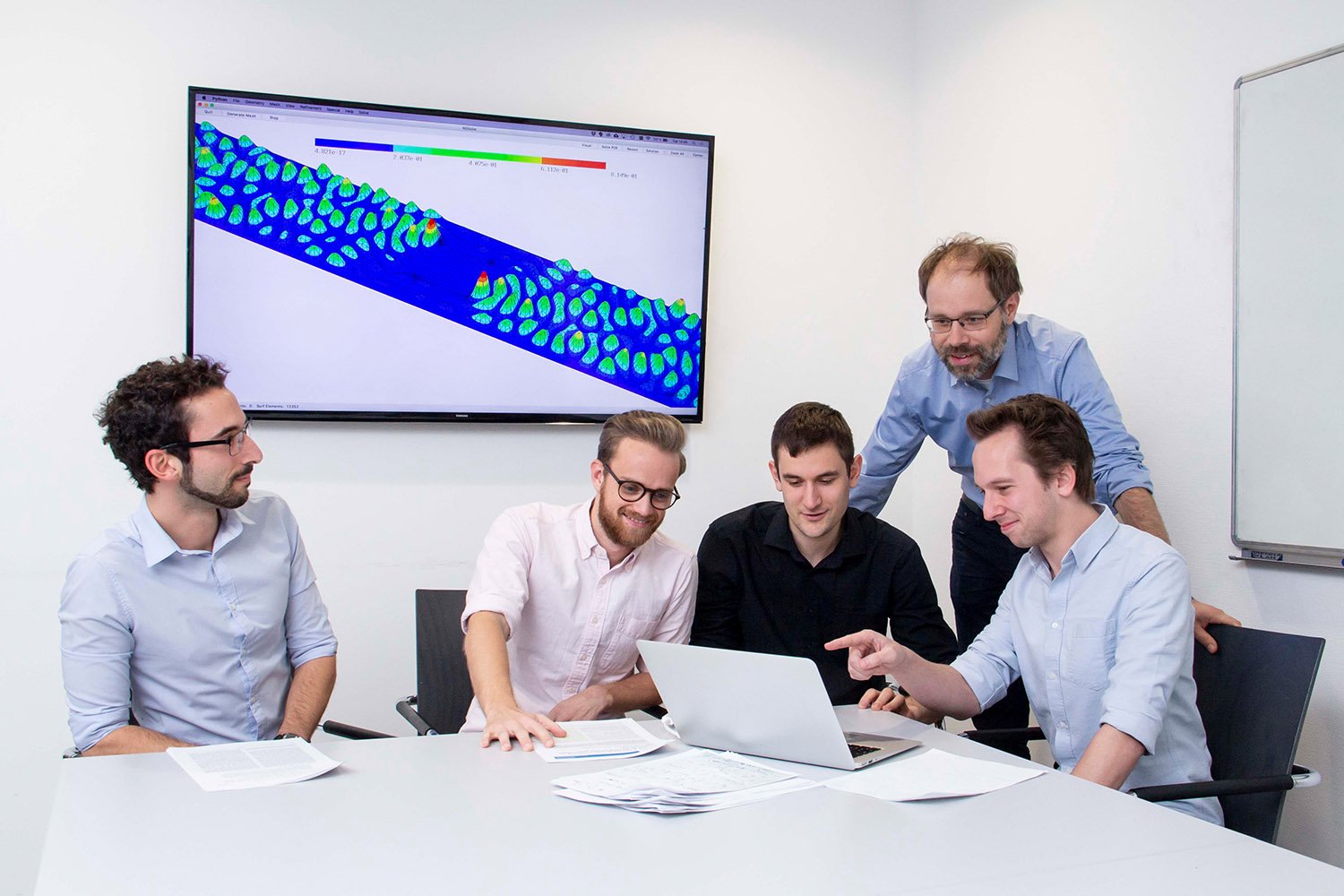

But scientists at TU Wien (Vienna) have now shown how virtue can be made of necessity: A special calculation method was developed to determine the perfect wave form to manipulate small particles in the presence of a disordered environment. This makes it possible to hold, move or rotate individual particles inside a sample – even if they cannot be touched directly. The tailor-made light beam becomes a universal remote control for everything small. Microwave experiments have already demonstrated that the method works. The new optical tweezer technology has now been presented in the journal Nature Photonics.

Optical tweezers in disordered environments

“Using laser beams to manipulate matter is nothing unusual anymore,” explains Prof. Stefan Rotter from the Institute for Theoretical Physics at TU Wien.

[ad_336]

In 1997, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for laser beams that cool atoms by slowing them down. In 2018, another Physics Nobel Prize recognized the development of optical tweezers.

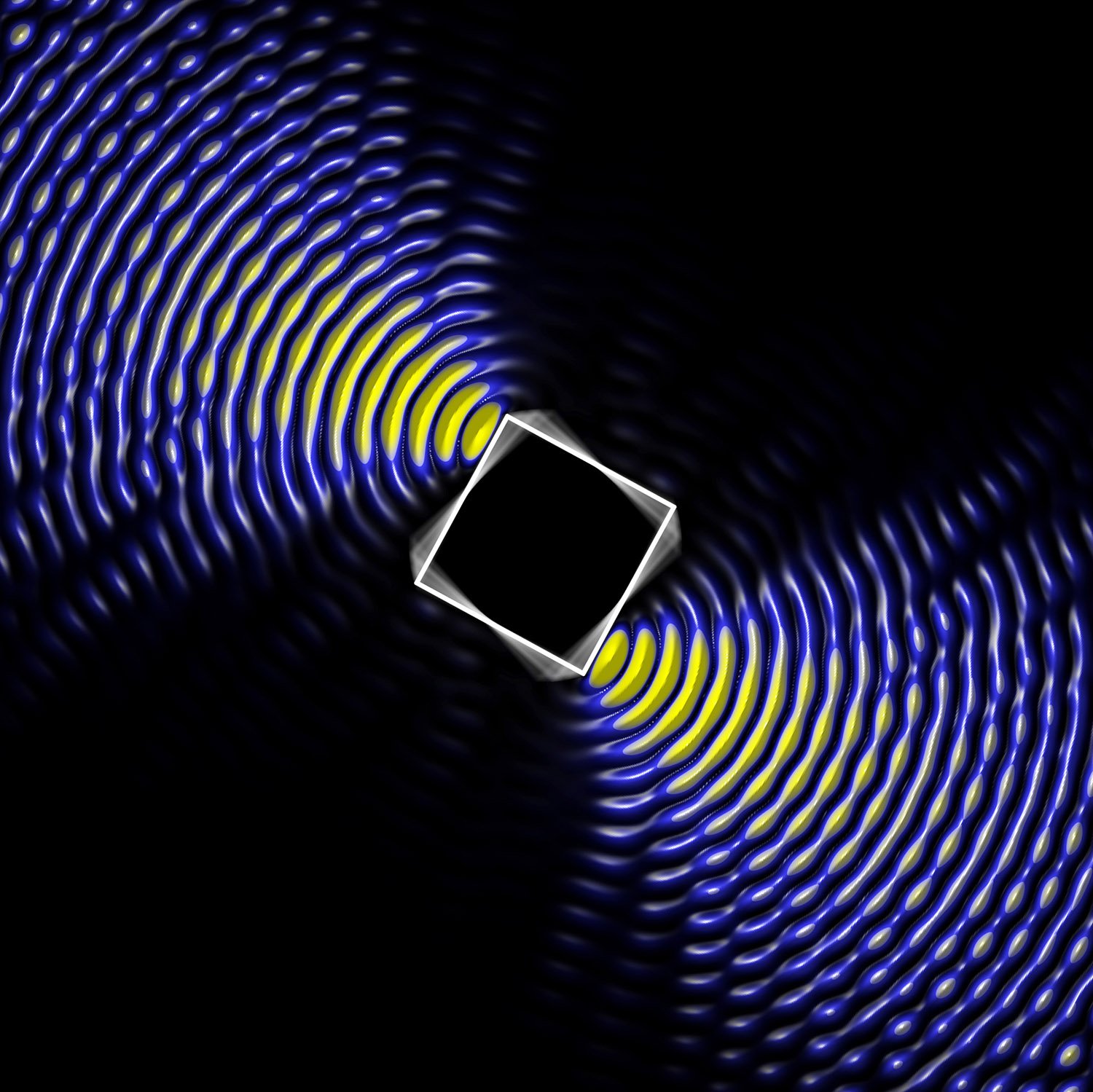

But light waves are sensitive: in a disordered, irregular environment, they can be deflected in a highly complicated way and scattered in all directions. A simple, plane light wave then becomes a complex, disordered wave pattern. This completely changes the way light interacts with a specific particle.

“However, this scattering effect can be compensated,” says Michael Horodynski, first author of the paper. “We can calculate how the wave has to be shaped initially so that the irregularities of the disordered environment transform it exactly into the shape we want it to be. In this case, the light wave looks rather disordered and chaotic at first, but the disordered environment turns it into something ordered. Countless small disturbances, which would normally render the experiment impossible, are used to generate exactly the desired wave form, which then acts on a specific particle.”

Calculating the optimal wave

To achieve this, the particle and its disordered environment are first illuminated with various waves and the way in which the waves are reflected is measured. This measurement is carried out twice in quick succession.

“Let’s assume that in the short time between the two measurements, the disordered environment remains the same, while the particle we want to manipulate changes slightly,” says Stefan Rotter. “Let’s think of a cell that moves, or simply sinks downwards a little bit. Then the light wave we send in is reflected a little bit differently in the two measurements.”

[rand_post]

This tiny difference is crucial: With the new calculation method developed at TU Wien, it is possible to calculate the wave that has to be used to amplify or attenuate this particle movement.

“If the particle slowly sinks downwards, we can calculate a wave that prevents this sinking or lets the particle sink even faster,” says Stefan Rotter. “If the particle rotates a little bit, we know which wave transmits the maximum angular momentum – we can then rotate the particle with a specially shaped light wave without ever touching it.”

Successful experiments with microwaves

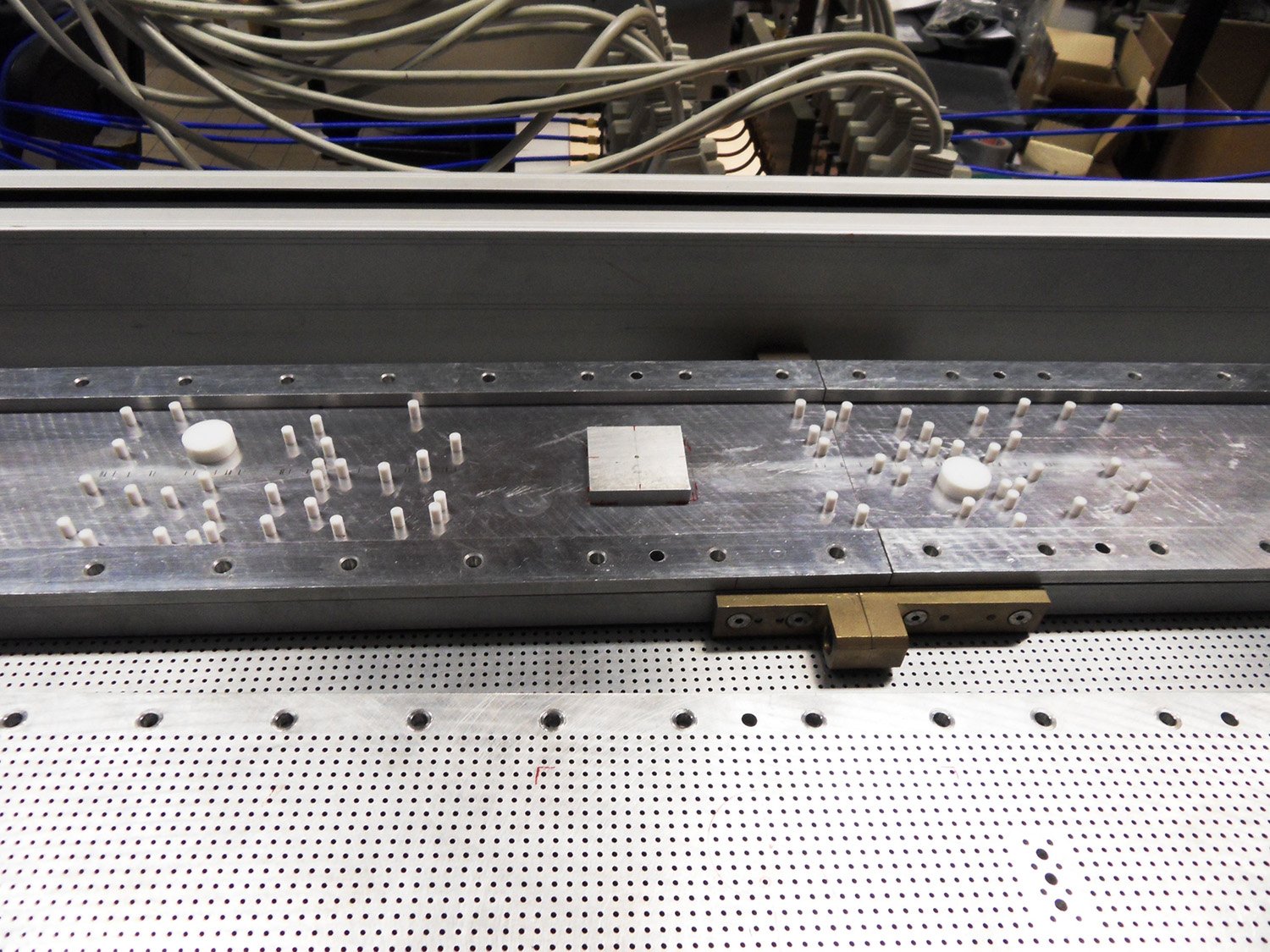

Kevin Pichler, also part of the research team at TU Wien, was able to put the calculation method into practice in the lab of project partners at the University of Nice (France): he used randomly arranged Teflon objects, which he irradiated with microwaves – and in this way he actually succeeded in generating exactly those waveforms which, due to the disorder of the system, produced the desired effect.

“The microwave experiment shows that our method works,” reports Stefan Rotter. “But the real goal is to apply it not with microwaves but with visible light. This could open up completely new fields of applications for optical tweezers and, especially in biological research, would make it possible to control small particles in a way that was previously considered completely impossible.”