How do plants and animals acquire their microbiota? Are hosts colonized by microbes from their surroundings or do parents transmit microbes to offspring? Understanding how animals acquire their microbiomes, especially microbial symbionts, is necessary to learn how environments shape host phenotypes via host-microbe interactions and whether hosts and their microbiomes represent an important unit of natural selection. In a study published in Nature Ecology and Evolution today, researchers from the University of Notre Dame (IN, USA), Natural History Museum (London, UK), the University of Auckland (New Zealand), and Theoretical and Experimental Ecology Station (Moulis, France) are presenting their research on the nature, strength, and consistency of vertical transmission in multiple coexisting host species in the wild from an animal phylum with exceptionally diverse microbiomes.

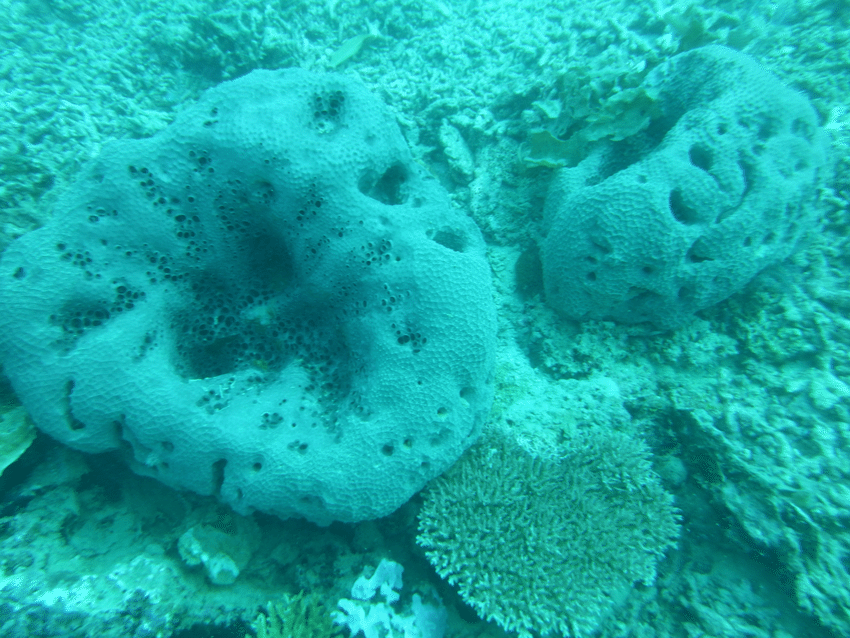

Studying vertical transmission in eight species of marine sponges—a phylum generally assumed to have coevolved with microbes, the authors find that vertical transmission is relatively comprehensive, but often undetectable. While larval sponges shared on average 44.8% of microbes with their parents, this fraction was not higher than the fraction they shared with nearby conspecific adults who were not their parents. Moreover, vertical transmission is inconsistent across siblings, as larval sponges from the same parent only shared 17% of microbes. Finally, the study found that vertically transmitted microbes are not faithful to a single sponge species: surprisingly, larvae were just as likely to share vertically transmitted microbes with larvae from other species.

“We were very surprised by the inconsistency and weak signatures of vertical transmission that we found, especially as many previous studies (including our own) have shown high host-microbe specialization”, said Johannes Björk lead author of the study from the University of Notre Dame.

“Moreover, electron micrographs have revealed that sponge oocytes, embryos, and larvae contain free-swimming or vacuole-enclosed endosymbotic bacteria that are morphologically identical to those found in the parent. However, this methodology cannot distinguish microbial species and so cannot provide conclusive evidence of vertical transmission in a system with exceptionally diverse microbiota such as in marine sponges”, he added.

[ad_336]

The absence of a large consistent set of microbes transmitted between a given parent and its offspring could have at least three explanations.

“Perhaps only a few symbiotic microbes are required to establish a functioning and beneficial microbiota; hence, parents might select and transmit just a few of the most important symbionts to offspring”, said Jose Montoya one of principal investigators of the study from the Theoretical and Experimental Ecology Station in Moulis, France.

“Parents may also benefit from varying the microbes transmitted to each offspring. Such variability might be important if offspring disperse long distances and settle in diverse and varying environments. This explanation is analogous to the idea that genetically diverse offspring are more likely to succeed than a genetically uniform cohort”, said Elizabeth Archie, also a principal investigator of the study from the University of Notre Dame.

[rand_post]

“The microbes transmitted to offspring might also be used as food to support the developing offspring, and in this case, microbial species identity might not be important”, added Johannes Björk.

“Finally, our study demonstrates that common predictions of vertical transmission that stem from species-poor systems are not necessarily true when scaling up to diverse and complex microbiomes”, he concluded.