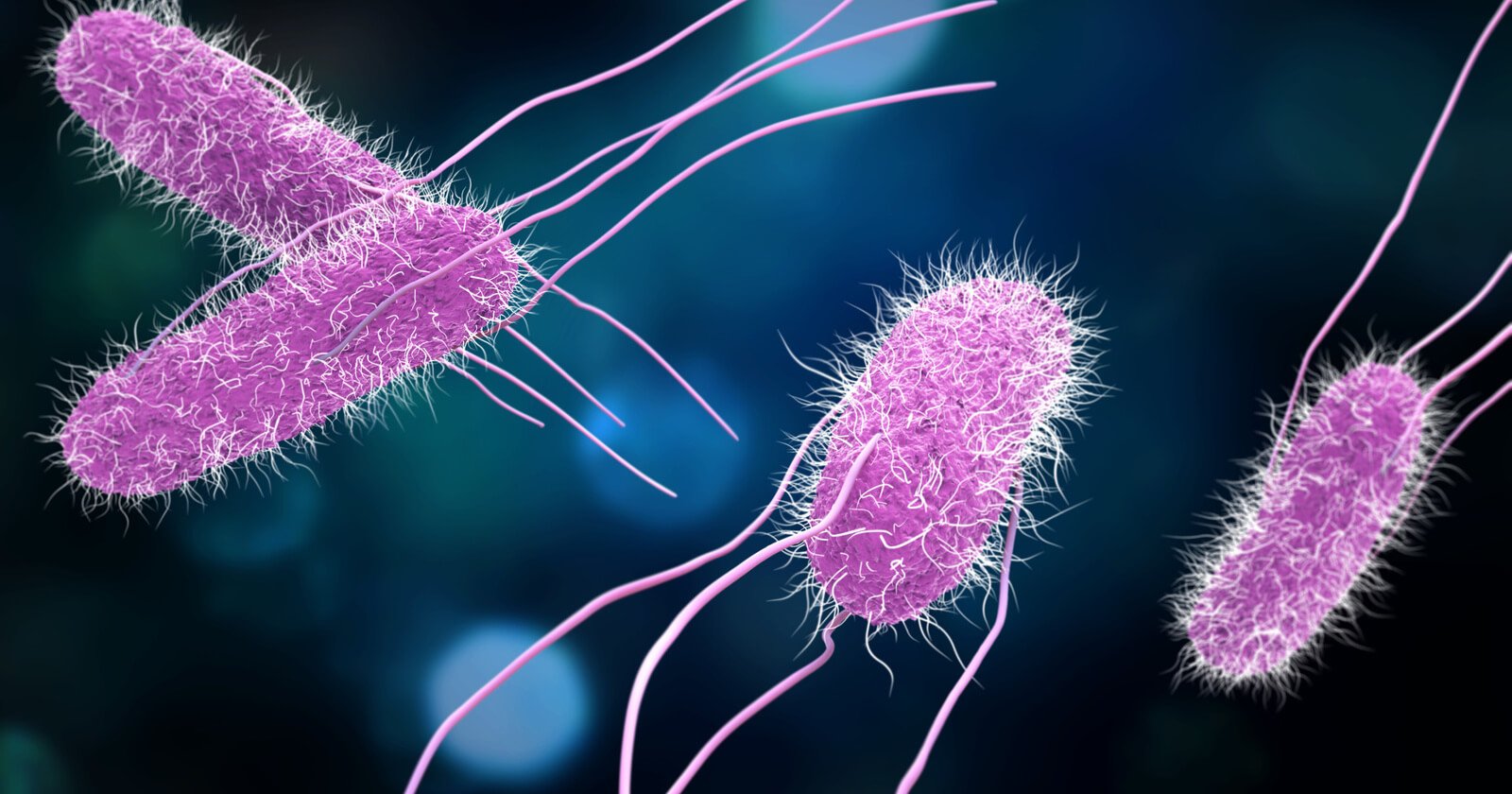

New research from the University of East Anglia shows how the human body powers its emergency response to salmonella infection.

A study, published today in the journal PNAS, reveals how blood stem cells respond in the first few hours following infection – by acquiring energy from bone marrow support cells.

It is hoped that the findings could help form new approaches to treating people with Salmonella and other bacterial illnesses.

Lead researcher Dr Stuart Rushworth from UEA’s Norwich Medical School, said: “Salmonella is one of the most common causes of food poisoning worldwide. Symptoms include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain and fever. Most people recover without treatment but young children, the elderly and people who have immune systems that are not working properly have a greater risk of becoming severely ill and it can be deadly. We wanted to find out how the immune system responds to Salmonella bacterial infection. Knowing more about how our bodies respond could help develop new ways to treat people with weak immune systems, such as the elderly.”

The UEA team collaborated with Norwich Research Park colleagues at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital (NNUH), the Quadram Institute and the Earlham Institute (EI), to study mitochondria – tiny powerhouses that live inside cells and give them energy.

They analysed the immune response to Salmonella bacterial infection, by using blood and bone marrow cells donated for research by NNUH patients.

They also worked with Salmonella infection experts from Quadram to study the way mitochondria moves between different cell types, using specialist microscopes and DNA analysis.

[rand_post]

They found that in the bone marrow where blood cells are made, support or ‘stromal’ cells were forced to transfer their power-generating mitochondria to neighboring blood stem cells.

Dr Rushworth said: “We found that these support cells were effectively ‘charging’ the stem cells and enabling them to make millions more bacteria-fighting white blood cells. It was not previously known how blood stem cells acquire the energy they need to mount an immune response to infection. Mitochondria are like tiny batteries which power cells. In response to infection, the immune system takes mitochondria from surrounding support cells to power up the immune response.”

As well as identifying how and why the mitochondria are transferred, the study discusses the potential impact on how infections are treated in future.

“Our results provide insight into how the blood and immune system is able to respond so quickly to infection,” said Dr Rushworth. “Working out the mechanism through which this ‘power boost’ works gives us new ideas on how to strengthen the body’s fight against infection in the future. This work could help inform how older people with infection might be treated. It is an essential first step towards exploiting this biological function therapeutically in the future.”

Director of Science at EI Prof Federica Di Palma, said: “This collaboration demonstrates how interdisciplinary research approaches are key to meeting the health needs of the future. The integrated efforts of three institutions with different scientific expertise has allowed us to understand important mechanisms used by our cells to fight bacterial infections, providing valuable insight into future therapeutic applications.”