Research over the course of the past decade has shown that global warming is more or less proportional to the total amount of CO2 released into the atmosphere. This makes it possible to estimate the total amount of CO2 we can still emit while having a chance to limit global warming to a certain level – a concept known as the remaining carbon budget. The simplicity of the notion has made it an attractive tool for policymakers, even though it is strongly dependent on the assumption of a linear relationship between global temperature rise and cumulative CO2 emissions due to human activity. Given that we are aiming to keep warming well below 2°C and preferably even below 1.5°C, this is an extremely important number to inform decision makers about how rapidly we have to bring our emissions down to zero.

As low-carbon policies and technologies continue to advance, policymakers, companies, and investors are increasingly relying on carbon budgets as a core component for analyzing the potential implications of a carbon constrained future. Over the past couple of years, several estimates were published that all differed to a greater or lesser extent due to reasons that were previously not well understood. We know that global warming is not driven by CO2 emissions alone – other greenhouse gases such as methane, fluorinated gases, nitrous oxide, and aerosols also affect global temperatures, and estimating remaining carbon budgets therefore also implies making assumptions about these non-CO2 contributions. This added uncertainty and decreased the use of the linear relationship between warming and cumulative emissions of CO2 for target setting.

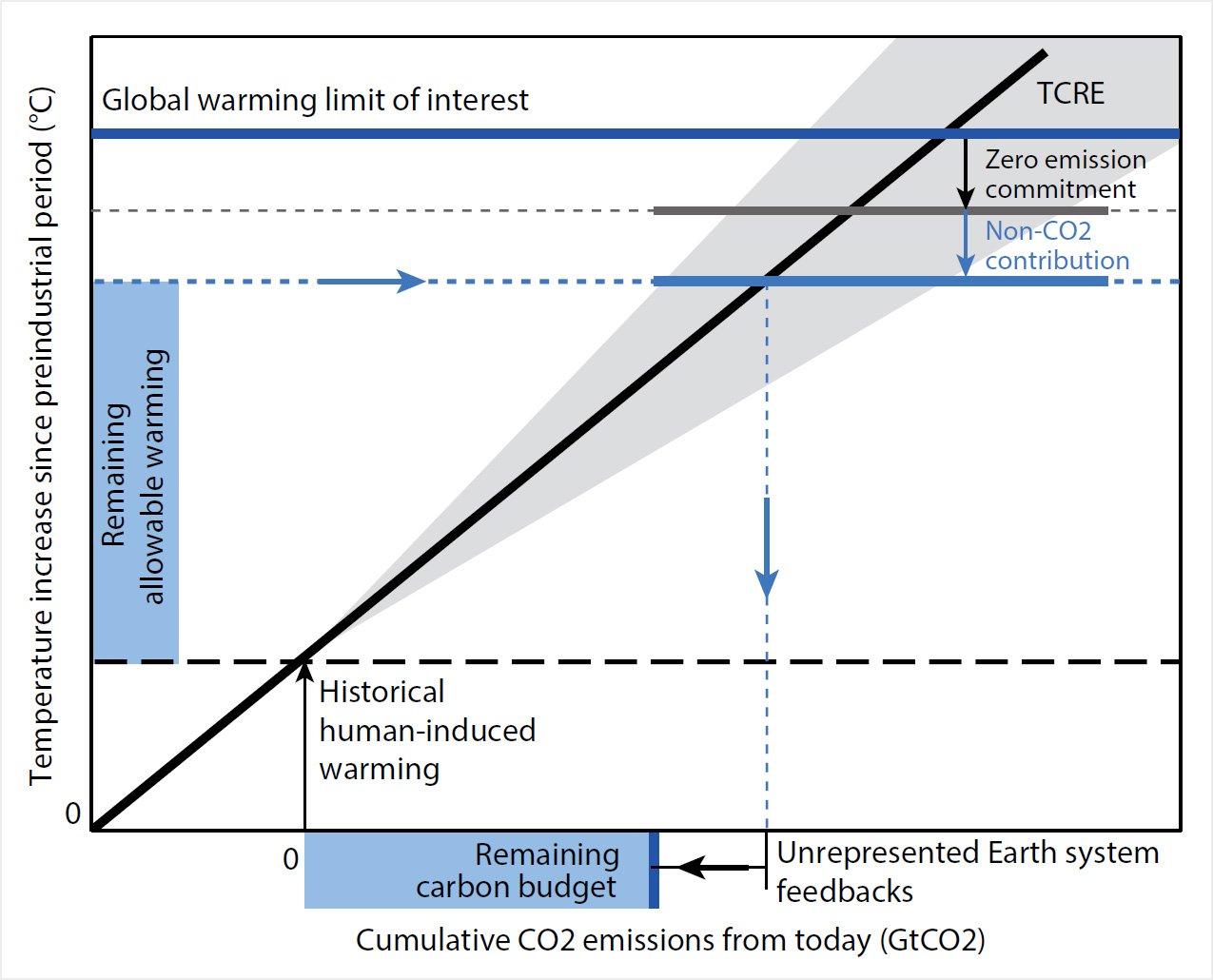

In their study published in Nature, researchers from IIASA and colleagues from among others, the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London, the University of Leeds, MeteoFrance, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, provide a way to understand and track changes in the remaining carbon budget. The framework they propose in their paper can also provide a way to better understand how this number might change in the future and contribute to a more constructive and informed discussion of the topic, while also facilitating better communication across disciplines and communities that research, quantify, and apply estimates of remaining carbon budgets. The study defines the size of the remaining carbon budget by five main factors. These are the amount of warming expected per ton of CO2 emission; the amount of warming observed until today; the amount of future warming expected from gases other than CO2; whether warming stops instantly once CO2 emissions get to zero; and an additional correction for whether there are any additional reinforcing cycles in the Earth system that have not been considered sufficiently.

“Our paper provides a new tool to clearly communicate up to date insights about carbon budgets. With the framework, changes can be pinpointed to single contributions that are much easier to understand. This should increase confidence in carbon budget estimates among policymakers, or at least their advisors, because changes in carbon budget estimates cease to appear to be random but rather are the result of clear progress of science in various areas,” explains Joeri Rogelj, a senior researcher with the IIASA Energy Program and lead author of the study.

According to the researchers, their framework can play a role in contextualizing new estimates in the future, even if they use alternative methods. It can also be used in combination with expert judgment to anticipate potential surprise changes in remaining carbon budgets and allow for a more independent assessment by drawing on multiple lines of evidence. A simplified version of this framework was already applied in the recent IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

“The remaining carbon budget is a key quantity for defining the challenge of limiting climate change to safe levels. With this paper, we can understand and track this quantity much better. If you carefully look at carbon budgets, they become easy to understand. The fog is lifted, so to speak, and shows even more clearly that the remaining carbon budget to limit global warming to safe levels is tiny – action in the next decade is essential to stay within it,” concludes Rogelj.