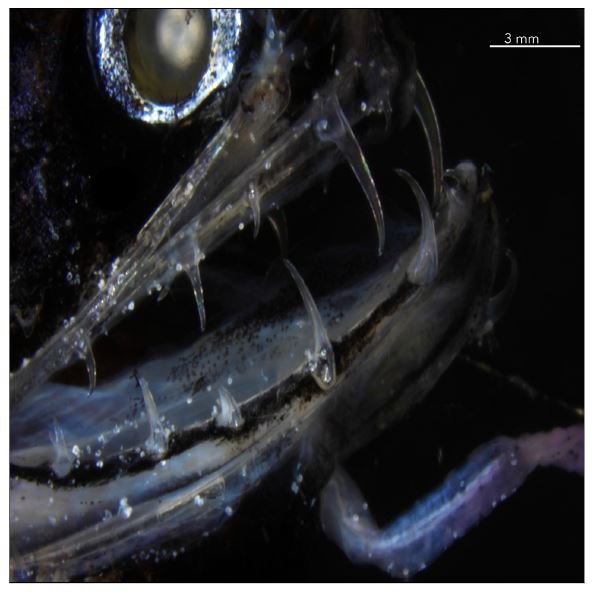

Off the coast of San Diego, 500 meters under the sea, pencil-sized sea monsters grin pitch-black smiles because their mouths are filled with transparent teeth. An investigation into this unique adaptation of deep-sea dragonfish (Aristostomias scintillans) revealed that their teeth evolved to reduce light scatter, allowing the fish’s wide-open mouth to effectively disappear right before its jaws snap onto its prey. A team of oceanographers and materials scientists describe the properties of the teeth June 5 in the journal Matter.

“Most deep-sea fauna have unique adapations, but the fact that dragonfish have transparent teeth puzzled us, since the trait is usually found in larger species,” says senior author Marc Meyers, who researches bioinspired materials at the University of California, San Diego.

“We thought that the nanostructure would be different, and when we looked at this, we found grain-sized nanocrystals embedded throughout the the teeth are responsible for this uncanny optical property.”

Despite measuring about 15 centimeters in length, deep-sea dragonfish are apex predators in their part of the ocean, feeding on smaller fish up to 50% of their size. The dragonfish’s most distinct feature is it’s extraordinarily large head full of fang-like teeth attached to a dark-skinned, eel-like body. The fish are so voracious that they tend to eat each other while researchers are in the process of collecting specimens.

Very few materials scientists are studying deep-sea creatures such as the dragonfish, but Meyers and graduate student Audrey Velasco partnered with Dimitri Deheyn, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who suggested the study. Their two groups teamed up with Eduard Arzt’s Lab at the Leibniz Institute for New Materials in Germany to analyse the nanostructure with a specialized electron microscope, operated by Marcus Koch. Birgit Nothdurft, a technician at the Leibniz Institute for New Materials, did the highly specialized preparation of the specimens.

[rand_post]

They discovered that transparency of the teeth is different from how other organisms have evolved this adaptation. First, they saw that dragonfish teeth, like human teeth, are comprised of an outer enamel-like layer and an inner dentin layer. The nanocrystals, about 20 nanometers in size, are dispersed throughout the amorphous matrix of the enamel, preventing any light that is in the environment from reflecting or scattering off the surface of the teeth. The teeth are are also relatively thin compared to other predatory fish, adding to this light scattering effect.

“Down at great depths there’s almost no light, and the little light there is comes from fish, such as the dragonfish, that have small photophores that generate light, attracting prey,” says Meyers. “But the dragonfish’s teeth are huge in proportion to its mouth–it’s like a monster from the movie Alien–and if those teeth should become visible, prey will immediately shy away. But we speculate that the teeth are transparent because it helps the predator.”

Based on this study, the researchers are now raising funds to create transparent materials inspired by dragonfish teeth, using a combination of nanocrystals and ceramics.