In the animal kingdom, survival essentially boils down to eat or be eaten. How organisms accomplish the former and avoid the latter reveals a clever array of defense mechanisms. Maybe you can outrun your prey. Perhaps you sport an undetectable disguise. Or maybe you develop a death-defying resistance to your prey’s heart-stopping defensive chemicals that you can store in your own body to protect you from predators.

Such is the case with most snake species of the Rhabdophis genus. Commonly called “keelbacks” and found primarily in southeast Asia, the snakes sport glands in their skin, sometimes just around the neck, where they store bufadienolides, a class of lethal steroids they get from toads, their toxic prey of choice.

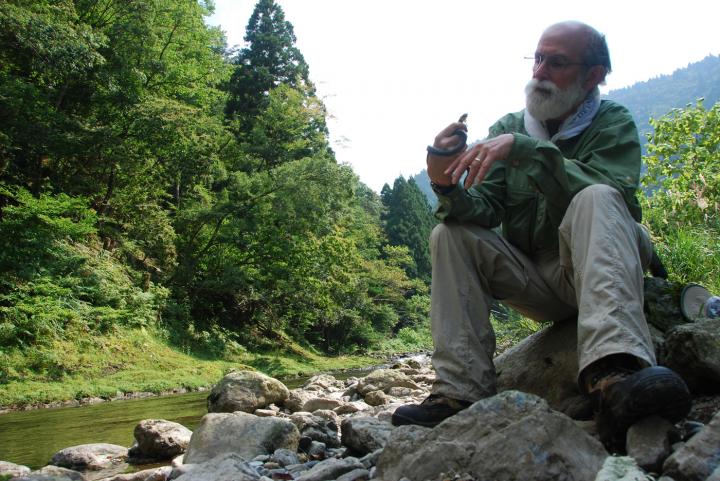

“These snakes bend their necks in a defensive posture that surprises unlucky predators with a mouthful of toxins,” says Utah State University herpetologist Alan Savitzky, who has long studied the slithery reptiles. “Scientists once thought these snakes produced their own toxins, but learned, instead, they obtain it from their food – namely, toads.”

[ad_336]

In a surprising twist, Savitzky and colleagues discovered not all members of the genus derive their defensive toxin from the same source. The multi-national team, consisting of researchers from USU; Kyoto University, University of the Ryukyus and Nihon University in Japan; the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Leshan Normal University in China; the National Pingtung University of Science and Technology in Taiwan; the University of Sri Jayewardenepura in Sri Lanka; and the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, reports a species group of the snakes, found in western China and Japan, shifted its primary diet from frogs (including toads) to earthworms.

The earthworms don’t produce the toxins; instead, the snakes also snack on firefly larvae, which produce the same class of toxins as the toads. Their findings appear in the Feb. 24, 2020, early online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is the first documented case of a vertebrate predator switching from a vertebrate prey to an invertebrate prey for the selective advantage of getting the same chemical class of defensive toxin,” says Savitzky, professor in USU’s Department of Biology and the USU Ecology Center.

[rand_post]

Given the distant relationship between toads and fireflies, he says, the dramatic dietary shift most likely involved a chemical cue shared by the toads and fireflies; perhaps the toxins themselves.

“This represents a remarkable evolutionary example of adaptation to compensate for the absence of defensive compounds following a shift to a new class of prey,” Savitzky says.