As Europe sizzles to yet another record heatwave, it is becoming more difficult for climate change sceptics to deny that our planet is warming at an unprecedented rate. But what are the consequences of these rising temperatures for our ecosystems and the natural resources that we derive from them?

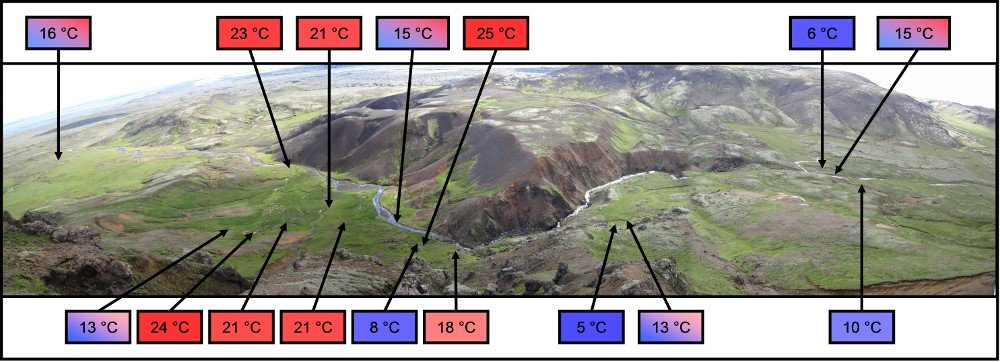

A team of researchers, led by Dr Eoin O’Gorman from the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Essex, have been studying the effects of increasing temperature on stream ecosystems in Iceland over the past decade. Their study site, the Hengill valley, lies in a volcanically active zone about 45 minutes’ drive east of Reykjavík. Here, they have sampled more than a dozen streams that differ in temperature (from 5 to 25 °C) due to geothermal heating of the groundwater in the area.

Over the past decade, the team have shown that some species, such as brown trout, cope surprisingly well with the higher temperatures in the area. This leads to bigger and more abundant fish in the warmer streams because they are very efficient at hoovering up all the available resources.

[rand_post]

However, it’s not all good news for the animals that live in these freshwater streams. The animals are all connected to each other through an intricate “food web” of feeding interactions. But the stronger feeding pressure from the fish and other abundant consumers in the warm streams leads to the loss of many species and their interactions, simplifying the food web.

Simpler food webs with fewer species and fewer interactions are more vulnerable to other perturbations. For example, the ecosystem is less likely to withstand an extreme event like a flood or a heatwave, which could cause it to collapse or shift to a completely new state.

[ad_336]

The team’s new results, published in Nature Climate Change, show that we can predict these effects of warming on food web structure using a simple mathematical model, based on the body size of the sampled organisms. So, if we can measure or predict how body size changes in warmer environments, then we will have a pretty good idea how the food web is changing as well. These sorts of predictive models are crucial for managing our natural resources in the face of global change.

The team’s next step is to test the generality of the result in other ecosystems around the globe. Another author on the paper, Prof Guy Woodward from Imperial College London, is leading a £3.7m project from the Natural Environment Research Council called the Ring of Fire. This project investigates similar geothermal systems around the Arctic Circle, including Greenland, Alaska, Svalbard, and Kamchatka. The team are also carrying out more controlled warming experiments in >200 artificial ponds to see if they find similar patterns to the ones they uncovered in Iceland.

A final word from Dr O’Gorman on their research: “Nature always finds a way to persist, no matter how stressful the conditions. But the ecosystems that remain may look very different from the diverse, pristine environments we have become accustomed to in our lifetimes”.